The fragility of cancer treatment... or lack thereof clipping

September 14th, 2020

This story begins the same way all great stories begin: on Twitter (ha…).

Last fall, as my ten-year high school reunion fast was approaching I reached out to one of my classmates on Twitter, which led to a few intriguing phone calls. Long story short, our conversation eventually led us to trade book recommendations. He recommended a few books by Nassim Taleb: a well-known mathematician, author, and "uncertainty" guru.

Taleb has a series of books on topics like luck, uncertainty, probability, human error, risk, and decision-making (e.g. Fooled by Randomness; The Black Swan). His latest explores natural systems which inherently benefit from disorder. He coins the term "anti-fragile" to describe these systems that aren’t just robust to variance, but derive increased benefit!

After dutifully following Taleb on Twitter (still waiting for my #FollowBack, alas…), I see him retweet a Wired article which describes ongoing adaptive therapy trials at Moffitt, noting that adaptive cancer therapy follows the pattern of anti-fragile systems.

Adaptive therapy has the potential to shift the current paradigm of cancer treatment. Although it’s gaining increased interest, it’s intriguing to see how quickly Taleb picked up on the concept, adding his hearty "it makes sense to me!" (of course, I paraphrase..)

So naturally I downloaded Taleb's anti-fragility preprint and I will explain the concept of anti-fragility below, and speculate how it may relate to adaptive cancer therapy. Let’s begin.

Random dosing strategies

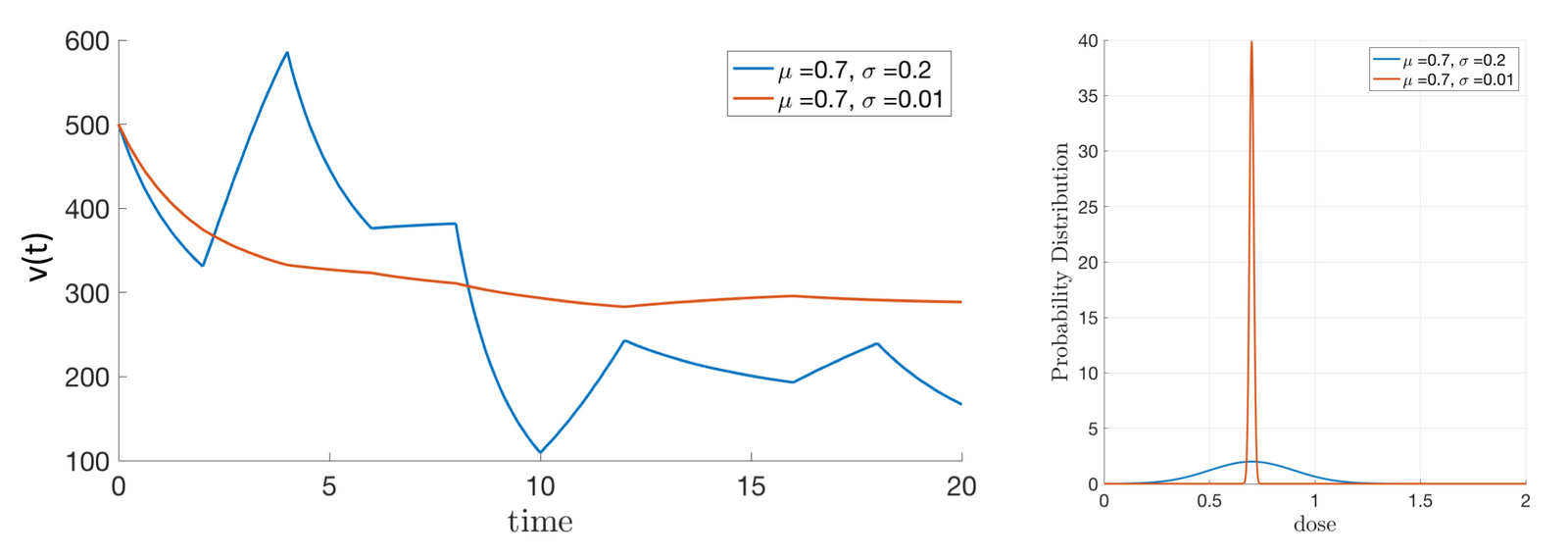

Below, we have patient tumor volume response, v(t), (left) to two dosing strategies (right). Rather than a pre-planned prescribed schedule we will draw random numbers subject to a probability distribution function, which gives us the probability of selecting a given dose, x: P(x).

The red dosing strategy is a narrow distribution (μ=0.7;σ=0.01). This results in a slow, but steady decline in tumor growth. Increasing the variance (μ=0.7;σ=0.2) leads to an overall improved outcome at the end of 20 months, but short term tumor growth (e.g., see t = 4).

With identical cumulative dose delivered over time, an improved response is shown for the P(x) with increased variance. Here, the system can be called "anti-fragile" because benefit is derived from increased disorder.

But let’s turn to some mathematical underpinnings of this anti-fragility concept. We can predict how variance in dosing affects tumor response by observing the curvature of dose response curves.

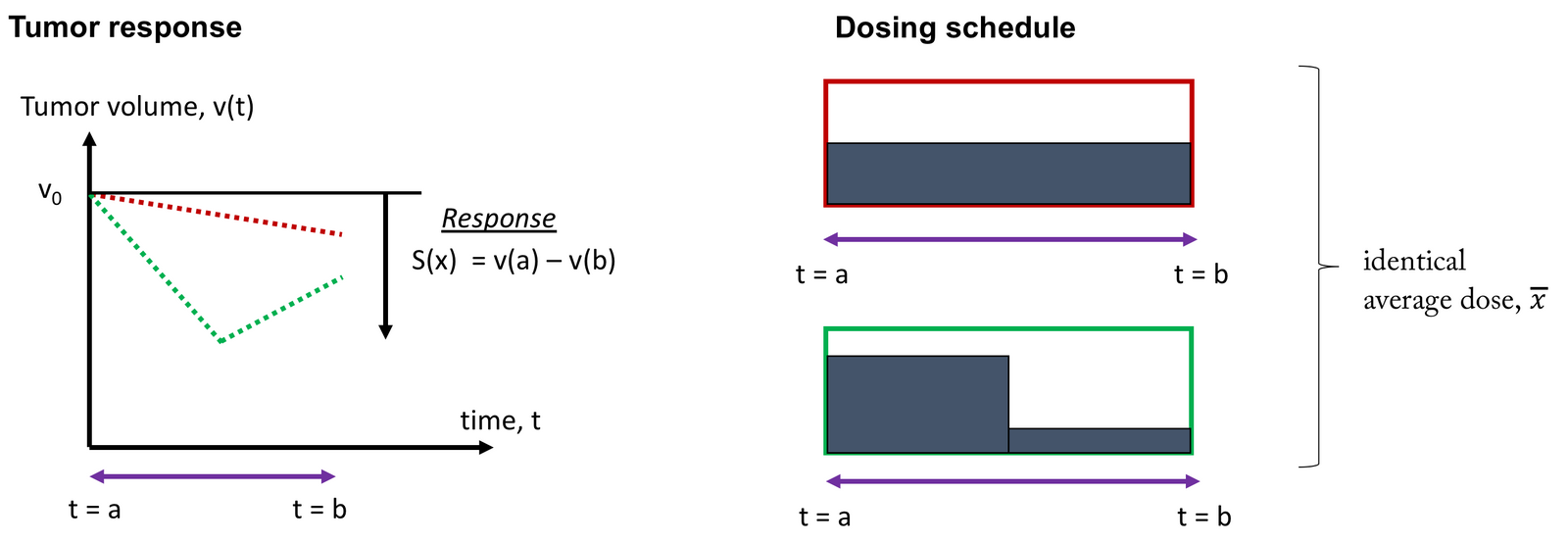

But first, let's consider a single cycle of therapy, below. Red shows the baseline: constant dose with zero variance in dose over time. Compare this to identical cumulative dose with increased variance (green). Here is the key idea: we can use a constant dose as a baseline to compare dosing strategies with increased variance.

Convexity & anti-fragile tumors

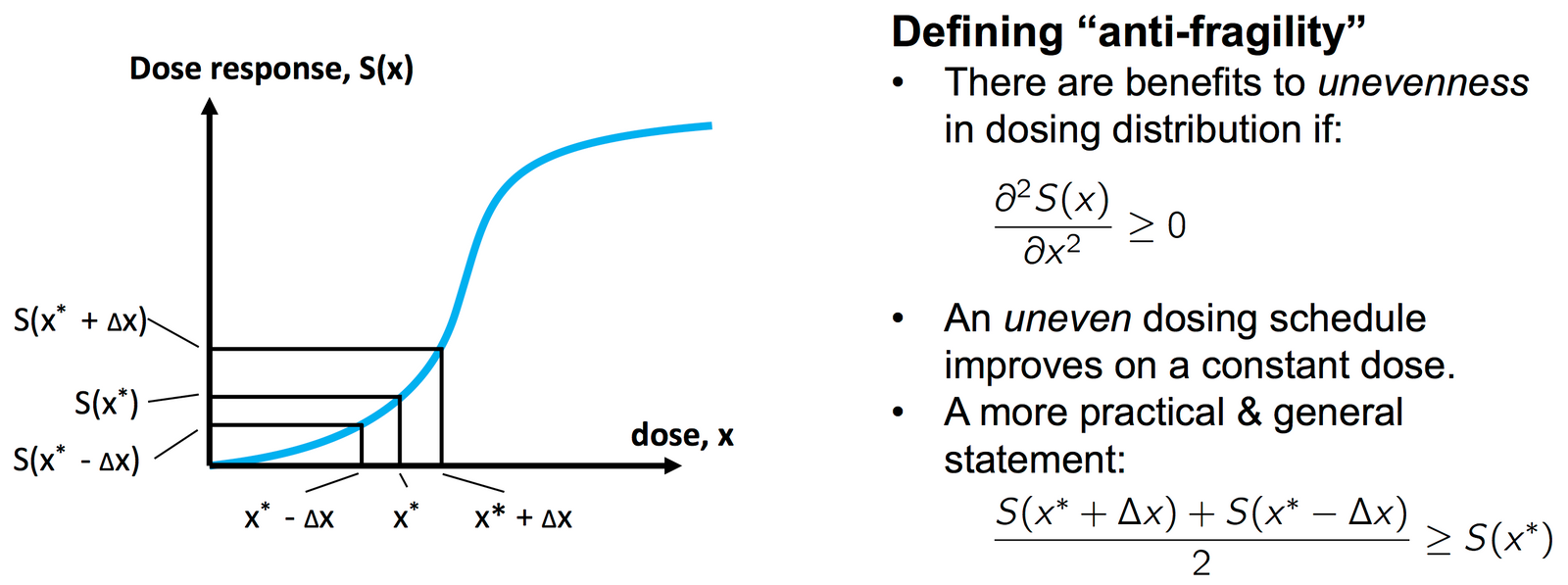

Let S(x) represent a dose response function that governs tumor response where S(x)=v(t=0)–v(t=T). In this way, increased S(x) represents more tumor kill. We want to compare response for a constant dose (x∗) to a dosing schedule which half time a little less (x∗−Δx) and half time a little more (x∗+Δx).

It can be shown that the second schedule (with higher dose variance) outperforms the constant dose if the curvature is positive.

This strikes me as a useful concept for 3 reasons:

- Anti-fragility allows us to determine if there an exists an improved schedule relative to the baseline of constant dose (holding cumulative dose constant).

- In general, sigmoidal dose-response curves should be expected to have convex AND concave regions. Sigmoidal dose-response curves are ubiquitous in medicine.

- It transforms complex dose response into regions of binary values: benefit or harm.

The first point is a practical one: it is likely easier to state whether an improved schedule exists (compared to baseline) than to determine the exact patient-specific optimal scenario. The second point proves the utility of this idea in cancer care: the curvature of cancer drug dose response should generally be mathematically "interesting." The last point is also practical: dimensionality reduction.

My hope is that it should not be too difficult to extend this analysis to compare dosing strategies with varied cumulative dose. In other words, if the curvature of S(x) is convex, can we increase variance and decrease dose to come out even? We also need to extend such analyses to include the effect of resistance... but that's for another blog post!

Keep in touch!