Beethoven's Heiligenstadt Testament and Emerging from The Abyss with Nietzsche

March 7th, 2020

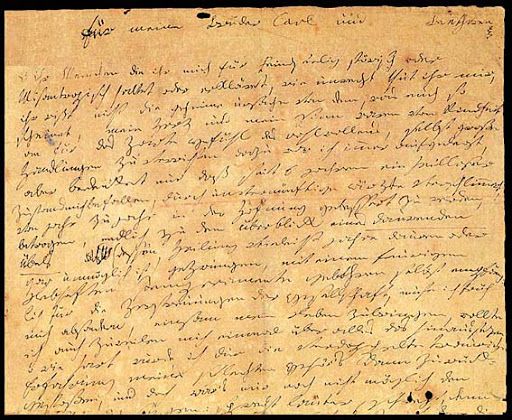

The Heiligenstadt Testament is an early will (and letter) written by Beethoven to his brothers Carl and Johann on 6 October 1802 concerning his increasing deafness. An addendum is dated 10 October 1802. It was discovered among his papers after his death and published (in German) in October 1827.

Almost thirty years old, Beethoven discovered he was losing his hearing. After failed attempts find a cure, his hope was shattered. Hearing he considered a composers indispensable tool! This, surely compounded by other trials, kicked off a "down-going" into the Abyss.

Unquestionably for many, living means to shoulder terrific burdens. Nietzsche makes his remark about the Abyss (in Beyond Good and Evil) just after cautioning the reader that someone who fights monsters risks becoming a monster himself. That can happen to the man of ressentiment. He’s convinced that his various disabilities are caused by someone or something out to get him, and that if only the scourge were eliminated from the world all would be well.

If this is your attitude, Nietzsche is saying, you’re going to get really good at ferreting out the nasty parts of life, wherever they might be hiding, and you’ll uncover one hitherto unrecognized injustice after another [1]. You may get to the point where you can see nothing but monsters [2].

"Beware that, when fighting monsters, you yourself do not become a monster... for when you gaze long into the abyss. The abyss gazes also into you."

Now, how should we interpret what Nietzsche says above, about the abyss gazing into you? How does Beethoven’s Heiligenstadt Testament reflect a mirrored snapshot in time of his "down-going".

The theme of Nietzsche's aphorism concerns the hazards of the life of the Free Spirit – the one who undermines existing values and creates new values of his own. Nietzsche seems to mean that if your highest value is truth and you pursue it at the expense of everything else, you risk encountering truths that cause you to question the value of life. We see this "questioning of life" in Beethoven’s will. This kind of truth can potentially drain you of energy and inhibit your will to power, which Nietzsche thinks is the highest value. For Beethoven, perhaps this value plays out in music.

The healthiest human being, Nietzsche believes, is one whose sheer love of life is so powerful that he or she enthusiastically desires the eternal repetition of everything that has happened and will happen – good, bad, and evil. The Eternal Recurrence! Such a person affirms life without qualification, absolutely. Only a person like this can afford to know all the truth. But how do you know whether you’re that kind of person? Or whether there are some truths about the human condition that, if you acknowledged them, would inhibit your love of life?

The only way to find out is to stare deeply into the Abyss of truth.

An Abyss is something that is bottomless: There’s no end to the search for truth. The issue with the Abyss: Where the bottom is for you? At some point you may find that the Abyss is staring back at you, and then you’ll know you’ve hit bottom.

What Nietzsche is saying could be construed as "Know your limits – be cautious." But I believe he is asking "How strong are you? You’ll never know unless you search the Abyss."

Beethoven found his Abyss and I believe the Heiligenstadt Testament was part of his Untergang (down-going). As Beethoven’s deafness worsened, his compositions seemed to flow from an infinite well of inspiration — an emergence from the Abyss.

Despite complete hearing loss, he completed — both in 1823 — his monumental Ninth or Choral Symphony, embracing Schiller's Ode to Joy and the Missa Solemnis (Mass in D), which he considered the crown — the best of all his compositions. The dedication on his last great work is unusual: "From the heart — may it speak to the heart." Beethoven passed away at the age of fifty-six, a quarter century of prodigious creativity after his Heiligenstadt Testament.

The Heiligenstadt Testament

For my brothers Carl and [Johann] Beethoven.

O you men who think or say that I am malevolent, stubborn or misanthropic, how greatly do you wrong me, you do not know the secret causes of my seeming, from childhood my heart and mind were disposed to the gentle feelings of good will, I was even ever eager to accomplish great deeds, but reflect now that for six years I have been a hopeless case, aggravated by senseless physicians, cheated year after year in the hope of improvement, finally compelled to face the prospect of a lasting malady (whose cure will take years or, perhaps, be impossible), born with an ardent and lively temperament, even susceptible to the diversions of society, I was compelled early to isolate myself, to live in loneliness, when I at times tried to forget all this, O how harshly was I repulsed by the doubly sad experience of my bad hearing, and yet it was impossible for me to say to men speak louder, shout, for I am deaf. Ah how could I possibly admit such an infirmity in the one sense which should have been more perfect in me than in others, a sense which I once possessed in highest perfection, a perfection such as few surely in my profession enjoy or have enjoyed — O I cannot do it, therefore forgive me when you see me draw back when I would gladly mingle with you, my misfortune is doubly painful because it must lead to my being misunderstood, for me there can be no recreations in society of my fellows, refined intercourse, mutual exchange of thought, only just as little as the greatest needs command may I mix with society, I must live like an exile, if I approach near to people a hot terror seizes upon me, a fear that I may be subjected to the danger of letting my condition be observed — thus it has been during the last half year which I spent in the country, commanded by my intelligent physician to spare my hearing as much as possible, in this almost meeting my present natural disposition, although I sometimes ran counter to it yielding to my inclination for society, but what a humiliation when one stood beside me and heard a flute in the distance and I heard nothing, or someone heard the shepherd singing and again I heard nothing, such incidents brought me to the verge of despair, but little more and I would have put an end to my life — only Art it was that withheld me, ah it seemed impossible to leave the world until I had produced all that I felt called upon me to produce, and so I endured this wretched existence — truly wretched, an excitable body which a sudden change can throw from the best into the worst state — Patience — it is said that I must now choose for my guide, I have done so, I hope my determination will remain firm to endure until it please the inexorable parcae to break the thread, perhaps I shall get better, perhaps not, I am prepared. Forced already in my 28th year to become a philosopher, O it is not easy, less easy for the artist than for anyone else — Divine One thou lookest into my inmost soul, thou knowest it, thou knowest that love of man and desire to do good live therein. O men, when some day you read these words, reflect that you did me wrong and let the unfortunate one comfort himself and find one of his kind who despite all obstacles of nature yet did all that was in his power to be accepted among worthy artists and men. You my brothers Carl and [Johann] as soon as I am dead if Dr. Schmid is still alive ask him in my name to describe my malady and attach this document to the history of my illness so that so far as possible at least the world may become reconciled with me after my death. At the same time I declare you two to be the heirs to my small fortune (if so it can be called), divide it fairly, bear with and help each other, what injury you have done me you know was long ago forgiven. To you brother Carl I give special thanks for the attachment you have displayed towards me of late. It is my wish that your lives be better and freer from care than I have had, recommend virtue to your children, it alone can give happiness, not money, I speak from experience, it was virtue that upheld me in misery, to it next to my art I owe the fact that I did not end my life with suicide. — Farewell and love each other — I thank all my friends, particularly Prince Lichnowsky and Professor Schmid — I desire that the instruments from Prince L. be preserved by one of you but let no quarrel result from this, so soon as they can serve you better purpose sell them, how glad will I be if I can still be helpful to you in my grave — with joy I hasten towards death — if it comes before I shall have had an opportunity to show all my artistic capacities it will still come too early for me despite my hard fate and I shall probably wish it had come later — but even then I am satisfied, will it not free me from my state of endless suffering? Come when thou will I shall meet thee bravely. — Farewell and do not wholly forget me when I am dead, I deserve this of you in having often in life thought of you how to make you happy, be so -

Ludwig van Beethoven

Heiligenstadt October 6 1802

Addendum

For my brothers Carl and [Johann]

to be read and executed after my death.

Heiligenstadt, October 10, 1802 — thus do I take my farewell of thee — and indeed sadly — yes that beloved hope — which I brought with me when I came here to be cured at least in a degree — I must wholly abandon, as the leaves of autumn fall and are withered so hope has been blighted, almost as I came — I go away — even the high courage — which often inspired me in the beautiful days of summer — has disappeared — O Providence — grant me at least but one day of pure joy — it is so long since real joy echoed in my heart — O when — O when, O Divine One — shall I find it again in the temple of nature and of men — Never? no — O that would be too hard.

— —

[1] First racism, then structural racism, then elitism, then heteronormativism, ableism, lookism, microagression….

[2] Someone who sees nothing but monsters can’t fail to develop an affinity with monsters. You may become the kind of monster known as a "moral saint."

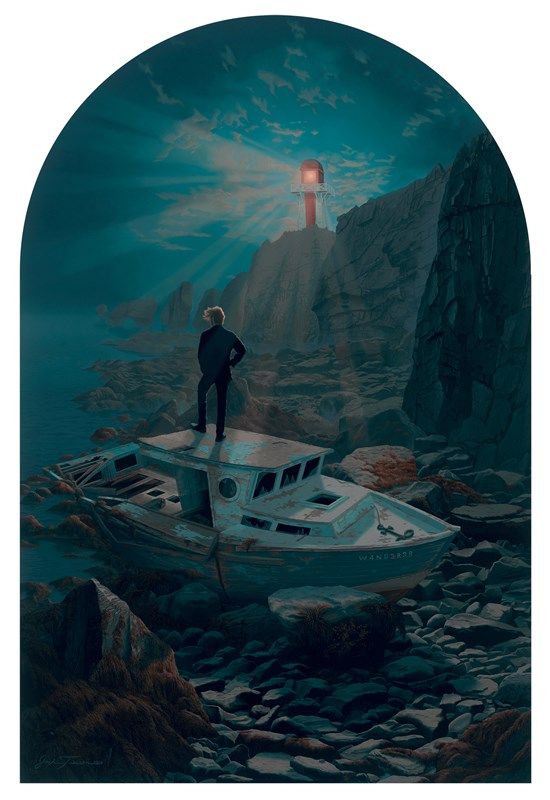

Painting "Dark Night of the Soul" by Josh Tiessen from Art Renewal Center. Photo of original Heiligenstadt Testament by Beethoven from lvbeethoven.com.

Keep in touch!